The remains of the Maya are indeed spectacular. The Maya are one of the great ancient civilizations of the world — complete with large city-states that boast monumental architectural complexes used by the aristocracy as a governing base as well as for public ceremonies. These centers were comprised of an array of people, including artisans patronized by the wealthy to produce goods used exclusively by the elite. Regional hamlets may have included nobles who interacted with merchants as well as those collecting tribute on behalf of the ruling centers.

Fig.1: Map showing the overlapping boundaries of the Maya region, which occupies both southeastern Mexico and several Central American countries. The eastern edge of the Maya region coincides with the intersection of Mesoamerica and the Isthmo-Colombian Culture Area (also called the Intermediate Area).

In order to understand the ancient Maya, archaeologists rely on context — the exact location of remains. Context affords us a glimpse into the past to understand the ancient systems of economic and political organization, the production of the arts, and the spiritual realm that influenced daily life as well as those in seats of power. Without context, we lose critical information about site development and regional alliances (see Introduction, pp.18-26).

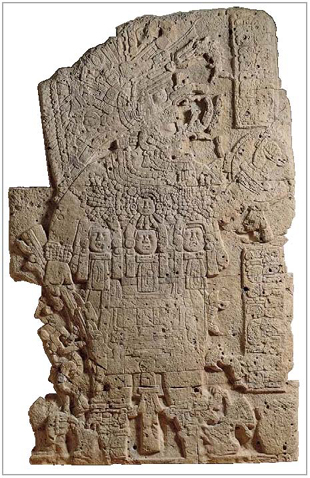

While archaeologists value context as an essential framework for site interpretation, art historians often pay scant attention to it. Since many museums have had policies of acquiring antiquities without much concern for context, this has effectively encouraged the antiquities trade, which runs directly counter to the interests of both archaeologists and the host countries of archaeological sites. One of the most acute examples of this is the illegal trade in Maya stelae (see below).

Fig.2: Stela D from the north side of the Great Plaza at Copán, Honduras, rising 12 ft beside an altar with a death god effigy, drawn by Frederick Catherwood in 1839 (Stephens and Catherwood 1841).]

The looting of archaeological sites throughout the Maya region is consequently of grave concern. It is through regional education and more broad reaching legislative efforts that we can combat this illicit activity. Central America makes a good case study for a critical analysis of looting and the respective legislative efforts precisely because the culture most often touted – the Maya – is not confined to one modern nation state; the US has had long-term legislation in place for Central America beginning with the 1972 Pre-Columbian Monumental Architectural Sculpture and Murals Statute. The US has also more recent legislation aim

Fig.3 (right): Early photograph of Temple 1 at Tikal, Guatemala, by the British explorer Alfred Maudslay in 1881-2 (Maudslay 1899-1902).

Broad considerations of the archaeologist: tourism and the antiquities market: Exploration of archaeological sites in Central America began in the early 1800s, including the well-documented findings of Stephens and Catherwood in the 1830s-40s (fig.2; see also papers in Boone 1993; Chinchilla 1998). By the late 1890s, sites in the region had received attention from the German, French, British and American scholarly communities, as exemplified by Alfred Maudslay (fig.3). In the US the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University became one of the major institutions backing research in the region, followed by the University Museum (now the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology), the Smithsonian Institution and the Carnegie Institution, among others. The goal was to understand the culture history of the Maya world. Subsequent research led to breakthroughs in the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphics, the astronWith the increased attention on the Maya world within Mesoamerica, many other cultural spheres have been subsumed within the broader label of Maya. These spheres include modern indigenous Maya groups, often viewed by the tourism industry as somehow frozen in the past (Arden 2004). Today, just as in the past, the diversity represented within Maya communities is tremendous and there is resistance to the holistic “lumping” of all Maya into one cultural sphere (see Mortensen 2006). Thus, there is a growing interest in how we as archaeologists recognize the impact of our research on not only our interpretations of the past, but also on the contemporary communities (Joyce 2003).

Subsumed within these considerations is the protection of archaeological sites in Central America. Precisely because ancient boundaries of the Maya world do not correspond to modern nation states, the countries of Central America must work together towards an integrated plan aimed at cultural preservation. This common goal has become increasingly apparent in recent years.

Fig.4: Map showing central portion of the ancient Maya region. Seven major sites have been designated world heritage resources by the United Nations UNESCO agency.

The largest sites or the most “unique” are those covered under the UNESCO World Heritage list. Those with a direct claim to the Maya, specifically the Late Classic period (AD 600-800), are most often celebrated on the tourist routes: La Ruta Maya program launched by National Geographic in 1989, now called El Mundo Maya, is a planned tourist circuit through the region to the most prestigious Maya ruins. In this way academic scholarship plays a vital role: it is this scholarship that defines how we perceive the ancient Maya and, thus, which areas are developed for tourism (Joyce 2003).

An emphasis on local education and involvement of local communities is one approach to site protection; it serves to integrate the communities aimed at sustainable tourism. It also promotes a dialogue of exchange regarding the significance of the past and the importance of context. These efforts have a solid up-hill battle, a battle against the trade in antiquities. While some have argued that the trade in antiquities would be eradicated if regional poverty declined (Matsuda 1998), I have argued that the trade is endemic, able to flourish precisely because the collecting community values aesthetics over context (Luke and Brodie 2006; Luke 2006; Luke and Kersel 2005; Luke and Henderson 2006). In fact, an analysis of the sale of Maya materials at Sotheby's from 1970 to 1999 (Gilgan 2001) confirms that archaeological context (the horizontal and vertical position of an artifact) has never been a consideration for the trade: objects are bought and sold regardless of whether their archaeological context is known. Contrary to growing talk of the value of context by the trade, there does not appear to be a higher market value for objects from the Maya region. Recent data indicate that this trend has continued (Gilgan, personal communication, 2005).

Fig.5 (right): Stela 15 from El Duende area of Dos Pilas before looting (photo: Stanley Guenter; Courtesy of Mesoweb).

What is more, Sotheby’s does watch the legislative efforts closely, changing an object’s attributed regional provenience depending on the current legislation. In 1991 an Emergency Agreement between the United States and Guatemala went into force for material from the Petén – area of the Guatemala Lowlands that was once the heartland of the most celebrated Maya sites. Sales at Sotheby’s did not decline, but the label of “Petén” was dropped, replaced by the more ambiguous “Lowlands” designation (Gilgan 2001). This shift of terms/vocabulary high

Looting the Maya world: The looting of the Maya World is real, and it is egregious. Monuments are smashed or deliberately sawed in parts, the parts reunited once in the collector’s home or institution. Architectural structures show massive scars from the rape of history: large trenches penetrate deep into the structures, undoubtedly evidence of those searching for royal tombs, a common feature in many Maya temples. Once found the tombs are ransacked by looters who take the perceived marketable items, leaving the rest behind, often scattered across the landscape, broken into pieces.

For many years, looting operations were believed to be clandestine in nature. In recent years this trade has taken on a new face (or this face has now been exposed): an “order” market. In 1997 National Geographic published a piece by David Stuart on the royal graves at Copan, Honduras. Included in the issue were photographs of the finds — still in context — from the tomb. In February, 1998 the entire area was plundered (Agurcia 1998). The finds that were taken suggested that the people responsible for the looting had seen the National Geographic publication.

Stelae at Dos Pilas: Another example of this type of deliberate, focused looting comes from the site of Dos Pilas. El Duende Complex was the target, an area outside the main center commissioned by Itzamnaaj K’awiil (AD 697-726). Here on December 12, 2003, stela 15 was violated: the small scepter held by the main ruler was removed, leaving behind a gaping hole in the large monument (figs.5,6). This precise target indicates that there is a market for a specific part

Fig.7: Stela 14 from El Duende area of Dos Pilas before looting (photo: Stanley Guenter; Courtesy of Mesoweb).

Stelae at El Perú: The hacking apart of Maya sculpture is not new. Numerous Maya-style stelae exhibit evidence of the deliberate sawing-up of the monument and then the rejoining of parts. Many of these damaged, but at least “complete,” stelae can be found at the most prestigious museums in the United States: the two stelae portraying females at the Cleveland Museum of Art and a stela at the Kimbell Art Museum (fig.9), among others. Here the clean saw marks that cut through these stelae provide evidence of malicious plunder events and serve as tell-tale signs of how such large monuments were made portable.

Fig.8: Stela 14 from El Duende area of Dos Pilas after base was cut off by looters (photo: Stanley Guenter; Courtesy of Mesoweb)

Both of the stelae at the Cleveland Museum of Art represent royal women. Such public displays of women are rare in Maya monumental art, but are essential for our understanding of access to power. Rulers often traced their royal bloodlines (or perceived royal bloodlines) through the matrilineal line and in several cases, royal women appear to have founded dynasties. The iconographic representations of these

The only provenience given for one of the stela is “Mexico or Guatemala, Usumacinta River region, Maya style (250-900).” Given the importance of women and the relatively rare occurrence of their representation, the plunder of these stelae is particularly appalling. The other stela is attributed to El Perú:

"She originally stood in a plaza between depictions of men, one probably her husband, ruler of the provincial Maya town El Perú... According to hieroglyphic texts, her importance stemmed from her family background. She came from a ruling dynasty at another Maya center, Calakmul, that was more powerful than her husband's; through marriage, he probably gained potent allies."

The remaining part of the museum text details the stylistic details of the piece as a work of art and the information conta

ined within the hieroglyphic text. It was the work of Ian Graham

that proved that the stela was

ined within the hieroglyphic text. It was the work of Ian Graham

that proved that the stela wasFig.9: Stela 33, the mate of Stela 34, kept in the Kimbell Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. This sculpture, looted from the site of El Perú, displays a ruler standing with his scepter and tasseled shield. By wearing the regalia of the gods, the ruler is sanctified as the nurturer of his people. Limestone, 107-3/8 x 68-3/8 in., acquired in late 1960s (photo © Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas).

Another of El Perú’s stelae is at the Kimbell Museum in Forth Worth, Texas, acquired by the museum on the New York art market in the late 1960s

These stelae and others in museum and private collections around the world were acquired in the 1960s, a period of increased plunder in the Maya world. Clemency Coggins brought the situation to light in her 1972 article, “Archaeology and the Art Market,” published in Science. She published not only a critical summary of the problem, but also the photographs of cut-up stelae parts in suitcases! The result of Coggins' research and efforts led to the 1972 Pre-Columbian Monumental Architectural Sculpture and Murals Statute (discussed below). Yet, the market, at least the public market, made adjustments again. As Gilgan’s (2001) research points-out, the sales at Sotheby’s over the years have focused on movable objects with few monuments or parts of monuments put up for public auction.

Site Q: While not offered on the public market, Maya stelae continue to be looted, as the cases from Dos Pilas above indicate. The impact on scholarship from looting in the 1960s as well as more recent events is real. For example, in the 1960s a series of hieroglyphic texts (at least two dozen), presumably from such monuments or facades, appeared on the market. A number of museums purchased the sculptures, including the Art Institute in Chicago (fig.10). The decipherment of the texts on those monuments at Chicago described a prominent Maya center, known for years as the mysterious Site Q. Many of the texts were incomplete, yet epigrapher Peter Matthews, who looked at the corpus as a w

Fig.10: One of six known looted ballplayer panels that may have adorned a staircase at site Q. An inscription above the righthand ballplayer identifies him at Red Turkey, a name that also appears on two stela fragments at La Corona (fig.4), a site in the Peten region of Guatemala, in the Late Classic period. (Limestone, h. 43.2 cm x w. 25.1 cm; Ada Turnbull Hertle Fund, 1965.407) (photo © Art Institute of Chicago).

Suggestions had been made that La Corona was indeed Site Q, and in 2005 a discovery at the site of an in situ hieroglyphic text (finally) confirmed that La Corona was the mysterious site. In fact, it was the placement of the looter’s trench that led to the discovery of the hieroglyphic text by Marcello Canuto; as recounted by Guenter, “He’d been taking GPS points on a number of pyramids in the eastern part of the site so we could check them against our map. He had had trouble with his GPS unit and just set it on the side of a looters’ trench and decided to nose around. And that’s when he noticed the carved stone” (Guenter 2006). This find (with context) has at last placed the sculptures on the landscape in the antiquity, even if many of the two dozen sculptures remain “lost,” buried deep within the black market or in the private collections, perhaps bank vaults, of their “owners.”

Looting of Maya sites destroys more than just the hieroglyphic record. It destabilizes structures, exposing contexts that while unmarketable for looters, are precious windows into the past. The recent surge of research at the site of San Bartolo has redefined our understanding of early occupation and social and political life in the central Lowlands. San Bartolo had been the focus of numerous looting efforts: the large abandoned trenches exposed an early Classic Maya mural. The mural was in situ, now exposed to the elements. The chance find of the mural in a looter’s trench by William Saturno set in motion a large-scale research program backed by National Geographic. Subsequent professional excavation has uncovered the earliest known hieroglyphic text of the region, some 300 years earlier than previously documented.

This situation h

Fig.11: Two Ulúa style marble vases, one gold figure, and one jade hand of the Santa Ana Corpus (photo: courtesy of the Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University).

Ulúa Marble Vases: A final consideration for review here is movable materials. Ulúa marble vases (figs. 11-13) from the Lower Ulúa Valley of northwestern Honduras are among the most sought-after items on the antiquities market. Only a handful has been e

Fig.12: Two Ulúa style marble vases of the Peor es nada corpus (photo: courtesy of the Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University).

The prices for these vases are indeed high for material from the Ulúa region: ca. $60,000 per vase. The exposure of the region through academic scholarship, particularly links to the central Maya lowlands, is promoting the area in the trade and driving prices higher, particularly for ceramics. Yet, plunder continues, further obliterating what little is left of the archaeological sites in the area, many completely destroyed (Luke and Henderson 2006).

The market for Pre-Columbian movable materials – fancy jades and ceramics – is anything but quiet. Christie’s has opened a new auction house in Paris, France. Recent sales at Sotheby's in New York show values for a single polychrome vase between $200,000 and $250,000, and $1,575,500 for an Early Classic Maya Jade at Christie's in their November 2004 sale. Such prices have traditionally been reserved for materials from the Classical world. The cases presented here only scrape the surface of the truly tragic

Fig.13: Map of the Ulúa Valley and surrounding areas in Honduras and Guatemala (Luke 2005).

Recent debate: With all the looting and the rise in market prices, what can be done to ensure that sites are not looted? While the outspoken pro-trade, legal expert John Merryman and others contend that the trade in materials should be legal precisely because these objects constitute world cultural heritage and, thus, should not be controlled by the modern nation states that subsume the sites, this camp appears to disregard their own argument when it comes to the protection of archaeological sites. An object is an object, regardless of whether it has context or not. Yet an object can be a direct lens into the past if it, as well as its context, is preserved. This holistic approach emphasizes that context must be the primary concern, the study of the artifact a natural corollary. Thus the very paradigm that is often used as an argument to open trade in antiquities, to promote museum exhibitions for educational purposes, is in fact the key problem. The world archaeological record must be protected and yet this is frustrated by the trade, which is dead-set on backing statements that value the object over context, thus dismissing the importance of the archaeological site. This seems to deflate credibility more than it appears to help and points to the ignorance of not only those in the trade, but also those in the upper echelons making decisions.

This debate has been a long-standing issue with museum acquisitions, both from direct sale and from donations from patrons. The material from the Landon T. Clay collection in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston is an example specific to material from Guatemala (fig.14). In the late 1980s, the museum accepted a number of objects from Clay. Guatemala strongly believes that the material was looted from the Petén and, hence, should be returned to Guatemala. Restitution of the objects remains unresolved.

This standstill with Guatemala may change in coming years, particularly with the current spotlight on museums and their acquisition policies at auction and from donors. Both the MFA and the Metropolitan have been involved in detailed negotiations with the Italians, following the explosion onto the antiquities radar of the trail of former Getty Museum curator, Marion True (see Introduction, pp.22-24; and Case Study 2, pp.32-38). In February, 2006 the Metropolitan agreed to return twenty-one artifacts to Italy, including the celebrated Euphronios krater (pp.27-30). Subsequently, on September 28, 2006, the MFA Boston signed a similar agreement with Italian officials, resulting in the return of thirteen culturally significant objects such as the six-foot Greek marble statue of Sabina (Edgers and Pinto 2006). The Getty Museum, meanwhile, has returned some artifacts to Greece and Italy and has recently conceded its prize artifact, a statue of Aphrodite purchased for $18 million in 1988, which the Italians claim was looted from Morgantina in Sicily (see pp.32-38).

While the restitution of objects is the subject of an entire paper, if not book, some press statements on the issue highlight the troubling lack of concern of the trade, and perhaps much of the museum world, to context. Metropolitan Museum Director Phillip de Montebello, for example, laments the plunder of archaeological sites, but he clearly does not view the central importance of context as an archaeologist would see it. In an interview published in the New York Times (Kennedy and Eakin 2006), Montebello said, “It continues to be my view – and not my view alone – that the information that is lost is a fraction of the information that an object can provide…Ninety-eight percent of everything we know about antiquity we know from objects that were not out of digs.” His specific example related to the highly contested Euphronios krater: “How much more would you learn from knowing which particular hole in – supposedly Cerveteri – it came out of?” he asked. “Everything is on the vase” (Kennedy and Eakin 2006; see also Case Study 1, pp. 27-30). From an archaeologist’s perspective, these comments provide a nearly perfect illustration of the scant attention paid to context in the museum world. Yet a much fuller realization and acceptance of the direct relation between context — or its obscurance — and legal vs. illegal status of imported artifacts is urgently required, especially by museum spokesmen. If museums would be both informed about illegal artifact trade, and held accountable for avoiding the purchase of illegally smuggled artifacts, this would introduce a necessary criteria of illegal vs. legal context that all museum officials would need to learn.

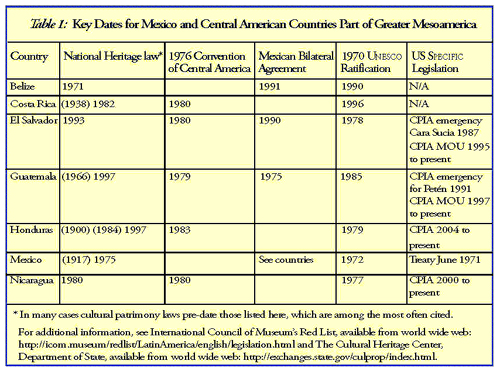

Legislation in Central America: In most cases, the countries of Central America including Mexico have had laws that govern cultural patrimony for over a century (see Table 1). The respective legislation in many cases corresponds to exploration and archaeological research by foreigners, usually under the auspices of a major institution, such as the British Museum or the Peabody at Harvard. For example, protection for the site of Copan in Honduras was triggered in 1836 by the work of John Lloyd Stephens, most likely by his purchase of the site, later revoked. Guatemala, too, had early laws, among the first in Central America (Chinchilla 1998). Over the years institutions wrestled against each other, all attempting to transport monuments back home. Faced with transportation difficulties, they developed a method of making plaster casts, thus allowing the remains to stay in place while bringing home a sort of replica. This would seem to be an ideal situation, yet many of the monuments have since been destroyed by the antiquities trade, such as monuments from Piedras Negras (fig.4), so that now only the plaster casts at the Peabody allow us to see their once intact state.

These early laws defined what constituted cultural

patrimony in the respective region as well as established guidelines

for foreign institutions wishing to conduct excavations. In most cases,

the finds were divided evenly between the host nation and the

sponsoring institution. This was certainly the case in Honduras during

the early decades of the 20th century. Yet with the increasing

awareness of archaeological context and need for site preservation,

countries began to change their positions, restricting the export of

any materials. For Honduras, the border was closed under a 1936 law,

yet material continued and continues to move clandestinely out of the

region (Luke 2006).

These early laws defined what constituted cultural

patrimony in the respective region as well as established guidelines

for foreign institutions wishing to conduct excavations. In most cases,

the finds were divided evenly between the host nation and the

sponsoring institution. This was certainly the case in Honduras during

the early decades of the 20th century. Yet with the increasing

awareness of archaeological context and need for site preservation,

countries began to change their positions, restricting the export of

any materials. For Honduras, the border was closed under a 1936 law,

yet material continued and continues to move clandestinely out of the

region (Luke 2006). In the late 1960s and the early 1970s, the international focus turned to the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illegal Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, and countries began to take a closer look at national ownership laws, particularly how (and if) they discerned between export regulations and full declaration of ownership. These two issues continue to be among the most important for prosecution of a case under US law.

For example, in 1984 Honduras put into place the Law for the Protection of Cultural Patrimony (legislative Decreto No. 81-84), firmly establishing both export and ownership provisions in the law. This law, like many laws in Central America [e.g., Guatemala (Decree 26-97) and El Salvador (Decree no.513)], recognizes unambiguously cultural patrimony as property of the state and enforces strict regulations for its excavation (i.e., application for work under a permit process). Yet these laws often allow for the transfer of cultural patrimony (for sale or as gifts) between private individuals and/or institutions within the country, provided that the material patrimony and its location are registered with the Ministry of Culture or designated government entity/institution. Thus, in theory, an active and legal trade is possible within the country. Honduras broke with this model in 1997 with the passage of Decree 220-97, which forbids the sale or transfer of cultural patrimony as well as the possession of cultural patrimony within state borders. The law is retroactive. The only provision is that objects may stay in collections until the death of the current patron, but they may not be transferred through inheritance.

Central American countries have also reached out to their neighbors in attempts to have regional cooperation to thwart the illicit traffic of antiquities over borders. All are party to the 1970 UNESCO and none have additional implementing legislation, as is the case with many “market” countries. As a party member, these countries of Central America as well as Mexico pledge to uphold their respective cultural patrimony laws. In addition, all, save Belize and Mexico, are party to the 1976 Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological, Historical and Artistic Heritage of the American Nations. Yet, Belize and Mexico have a bilateral agreement with each other, as does Mexico with Guatemala and El Salvador. Thus, while Mexico may not be party to the 1976 Convention, it has taken steps to ensure that those countries it shares borders with do have legal instruments that pertain to cultural patrimony.

Finally, an international convention that has been gaining favor once again is the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on the Return of Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects. UNIDROIT, unlike UNESCO, makes no distinction between plunder and theft, providing an opportunity for countries to pursue legal action under existing stolen property instruments. In the last six years both El Salvador and Guatemala have become parties.

Legislation from the US perspective: As shown in the few examples provided in this paper, the United States is one of the largest market countries for antiquities from Central America and Mexico (as well as other materials from around the world). While sales throughout Europe may be (and probably are) higher than those in the US, Europe isn’t a country per-se and, hence, can’t be regulated under the guise of a nation-state model. Even if the European Union decided on broad-sweeping legislation, Switzerland, a key node in the antiquities trade, is not a member state. Switzerland is often touted as the key place to launder title because, until recently, the Swiss allowed looted antiquities to pass through their borders, thus providing an opportunity to mask the dirty history of an object. The close proximity of a large US market for materials from Central America and, particularly, Mexico makes the United States desirable for those trafficking in antiquities. The traditionally porous US border with Mexico has made for an easy transit route, as have the multiple direct shipping routes and direct airline flights from Central America to US ports of entry.

With the vibrant trade, it is no surprise that the US does have a number of legal instruments that pertain to cultural patrimony in Central America and Mexico. Two of these are over thirty years old: the 1970 Treaty of Cooperation between the United States of America and the United Mexican States Providing for the Recovery and Return of Stolen Archaeological, Historical and Cultural Properties and the 1972 Pre-Columbian Monumental and Architectural Sculpture and Murals Statute (date of enforcement June 1 1973). The US-Mexico Treaty is more comprehensive than the Pre-Columbian Statute for material within the boundaries of Mexico. In addition to archaeological goods, the US-Mexico Treaty covers historical materials, which includes colonial period materials, demand for which is growing. Furthermore, Mexico has a national ownership law and it has been upheld by the United States under the National Stolen Property Act of 1946, known as the McClain Doctrine (see below).

The 1972 Pre-Columbian Monumental and Architectural Sculpture and Murals Statute is particularly effective, at least in theory, because it is regional in coverage, not specific to nation-states, unlike the US-Mexico Treaty or the various bilateral agreements with the US (see below). The focus of a statute on the material, rather than the state, alleviates the need to correspond ancient and modern boundaries. The specific nature of this statute is clearly presented in the US Code of Federal Regulations for Customs Officers, the actual implementing documents. Yet in reviewing the US Customs and Border Protection, “Special Rules of Protected Cultural Property” section (p. 14), specific country names have crept into the guidelines. With regard to this statute the compliance publication states that such materials “are the product of a Pre-Columbian Indian culture of one of the following countries: Belize, Bolivia, Columbia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Peru or Venezuela…” In addition to problems with translation from one document to the next, this highlights a fundamental attempt to favor modern boundaries over ancient ones, undermining the very nature of the statute.

The Pre-Columbian Statute does not cover movable items that are not sculptures or murals or parts there of. Yet these materials constitute much of the archaeological record: ceramic vessels, ceramic figurines, stone tools, stone jewelry, stone vases, and items made of shell. There is additional legislation in the United States for these types of objects. Unlike the Pre-Columbian Statute, however, such legal instruments are country specific.

CPIA and MOU: Under the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act, the implementing legislation for the 1970 UNESCO Convention in the United States, there are several ways of stopping material at the US border. The CPIA implements the 1970 UNESCO articles 7b and 9. Article 7b focuses solely on stolen materials; that is, materials that have been inventoried from a collection and/or excavation. The US agrees to stop stolen materials from any state party to the 1970 UNESCO Convention. Article 9 deals with materials that have been plundered and, hence, lack context. Yet, in order for material to be stopped at the US border, the modern nation state where the material in jeopardy resides in the ground must formally ask the US for a bilateral agreement or what is commonly referred to as an MOU (Memorandum of Understanding) (see Luke and Kersel 2005).

The process of requesting a MOU is not easy. A country’s request must address four points: pillage is a problem; efforts are in place to combat pillage; the US market is part of the problem; and the history in question is valued by the international community (e.g., interest in archaeological research in country and/or loans of material for international exhibitions). A request must be submitted via diplomatic channels, usually transferred in writing to the in-country US Embassy, but it may also be transferred to the US via the respective country’s Embassy in Washington, D.C., among other channels. The request is then reviewed by the Cultural Heritage Office at the US Department of State and transferred to the Presidential Cultural Property Advisory Board – a group of experts in the fields of museums, archaeology, anthropology, and the trade. The committee then recommends that an agreement be made or not. The appointed decision maker makes the final determination. If the decision is favorable, the country enters into an agreement, a formal MOU. This process can take 2-6 years (or more) to complete; a MOU is a five-year agreement that may be renewed multiple times. An emergency agreement for a specific area may precede a formal MOU. At this time, a number of Central American countries have MOUs (see Table 1). All such agreements cover Pre-Columbian materials most likely to be pillaged, but do not cover Colonial material (provision under the “ethnographic” category of the CPIA), which the agreements between the United States, Peru and Bolivia do cover.

Within the CPIA there is room for multilateral agreements with other nation states. Such an option has never been presented by a group of countries. Central America makes a good first case precisely because many countries already have MOUs with the United States. The benefit of a regional agreement would be to alleviate the process of determining ancient vs. modern boundaries. One key issue for Central America would be the implementing date for a multilateral agreement, given that the various MOUs have a number of different dates of enforcement.

A more clear-cut approach would be for countries that share ancient cultural regions, such as those in the Mediterranean, to apply for a multilateral agreement from the outset, alleviating the country-by-country process and providing for more effective coverage. For example, Greece and Turkey could approach Cyprus and Italy – countries with MOUs – and ask for a concentrated diplomatic effort with a region-wide approach. Alternatively, these countries could side-step the CPIA process entirely and focus on broad-sweeping legal instruments, such as the Pre-Columbian Statute, geared towards specific types of objects, monuments, etc.

Proper documentation: Both the CPIA and the Pre-Columbian Statute mandate satisfactory evidence. What constitutes proper documentation under the Pre-Columbian Statute is not specified. Yet, when read closely, satisfactory evidence under the CPIA allows for a good faith statement that “to the best of [the importer’s] knowledge, the material was exported from the State Party on or before the date such material was designated” under the respective legislation. Ideally such statements should be corroborated, really probing whether the importer is naïve enough not to understand the egregious nature of plunder in so many source countries. Making such claims is becoming harder and harder as more and more legal cases involving key figures and institutions are highlighted in the mainstream press. Furthermore, such naivety is clearly not present in the dealing community. In fact, as Mackenzie's recent chilling account describes, dealers know exactly what they are up against and continue to operate, hedging their bets. An excerpt from Mackenzie's (2005: 107) book highlights this sentiment:

[Would it be fair to say that if the information was available, where the objects were found, that would be of interest to you?]

Of course it would be of interest to me, and I desperately want to give it, but I would have to caution it with “said to be" or “allegedly from" because otherwise I could lose it. It's obvious…

[What you can do, I think, is improve your mechanisms for recording and passing on provenance information.]

I've tried and I get hit for it. I've destroyed some of it out of fear. (Geneva Collector I)

The bottom line is that context doesn’t appear to be valued enough for collectors to retain it when it is known and/or ensure that objects have it, and they will go through many hoops to get what they want: the object and/or money for the object. Again, an excerpt from Mackenzie's book highlights this point:

If a collector wants a particular piece, a collector wants a particular piece. That's why you'll find a lot of these sort of works are literally going to an end collector who might have employed a dealer to start doing the work, the searching for them. For instance, a person might say look, they want a Maya head, they want this, this, this, and this. And then they'll go off and they'll ask dealers and a dealer will know someone who knows someone, and the next thing one gets pulled away. (Melbourne Dealer 2; from Mackenzie 2005: 144)

Court Cases: A violator of the CPIA or the Pre-Columbian Statute in the United States is required to give over the materials. These instruments are civil, not criminal. Under a positive criminal prosecution the defendant may serve jail time. A number of smuggling statutes and the National Stolen Property Act of 1946 are criminal, and over the years they have been used against violators of cultural property.

The National Stolen Property Act (NSPA) received renewed attention after the conviction of Fredrick Schultz in 2003, the former President of The Association of Dealers in Ancient, Oriental and Primitive Art. In United States vs. Schultz, Schultz was convicted of dealing in stolen goods from Egypt. This decision affirmed the McClain case (United States vs. McClain) from the late 1970s involving Mexican material. While the McClain doctrine is the most cited, another case, also in the 1970s, has also been successfully prosecuted under the NSPA, United States vs. Hollinshead. In this case Hollinshead was found to be in violation of the Guatemalan ownership laws for the taking of a Maya stela from the territory of Guatemala. The defendants were part of a smuggling ring moving Maya stelae out of Guatemala through the Belize border and into the United States. The stelae were cut-up into pieces and transported in boxes marked “personal effects” (Gerstenblith 2001: 214, fnt. 65).

Fig.14: Maya vase of the Landon T. Clay collection, which may have been looted from the Petén region of Guatemala. The vase is currently kept at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Late Classic period AD 725-760 (photo © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Gift of Landon T. Clay).

In all of these cases the court found that each country – Egypt, Guatemala, and Mexico – had sufficiently strong and clear language in their cultural heritage legislation that ownership of all cultural heritage was indeed vested in the nation state. Trafficking in cultural patrimony without permission from the respective state is, then, dealing in stolen goods. Many countries do have equally strong ownership laws in addition to export laws. The real crux of the issue is how such criteria will be enforced at the US Border. With three successful cases, the most recent in New York City – the heart of the US antiquities trade – can the US now enforce the cultural heritage ownership laws of other countries at our borders?

In addition there are a number of smuggling statutes that can certainly be used to detain goods, the final investigation determining whether the goods will be seized. Like the National Stolen Property Act, violation of smuggling statutes is criminal. Such statutes focus on falsifying information, such as declaration of artifacts as replicas or craft goods, altering original documentation or artifacts as well as false declaration of value or country of origin. The 2003 case of United States vs. Douglas Hall involved violation of 18 U.S.C. § 371, 476, 545, and 542 – all smuggling statutes. The importer, Douglas Hall, had falsely declared the value of merchandise from Honduras (279 objects declared at $37) at entry in Miami, violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2 and 545. His attempt to sell the materials, now valued at $11,000 at his shop “Accent on Wild Birds” in Ohio, placed him in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 371 (specific to the sale of material imported in violation). While Hall did not work alone (a Guatemalan national was with him as well), the court found that Hall was the organizer of the criminal activities. Hall appealed the case. In 2004, his appeal was denied.

There are many more examples of violations of smuggling statutes. The Hall case is a good one because it highlights that trafficking of cultural patrimony can be thwarted using a number of US legal instruments that aren’t necessarily specific to cultural patrimony. The trafficking of objects involves multiple stops. In many cases what is illegal in one country is legal in the next, yet upon transfer to a third party, the material is again in violation of law. Hence, people try to launder title in many different countries. The frequent movement of archaeological goods, then, implies a long trail of paperwork, paperwork that may have false declarations.

Conclusions: In conclusion, the current situation is thus: there is a large problem of looting in Maya areas as well as throughout the globe; there is legislation in place to combat this problem; yet, there is a thriving antiquities market, regardless of the legal instruments both in the source countries and the market countries. What all the case studies and legal analyses come down to is location. Where was the object looted from, and, if we don’t know, how can we stylistically link it to a region? One US instrument – the Pre-Columbian Statute – focuses on the objects first, disregarding the modern boundary question. Yet in the 2004 Customs guidelines modern country boundaries have been introduced, suggesting that for seizure you need verification of the country of origin. Furthermore, many of the instruments specific to cultural patrimony provide wiggle room for those folks dealing in cultural property.

The problem, thus, is two fold: the market drives looting and there is not a strong will to regulate the market with professional standards. That is, if the legislation specific to cultural heritage or even the plethora of smuggling statutes were enforced at the borders of source countries or market countries, illicit material would stop flowing through the market place. If law enforcement actually demanded real satisfactory evidence, people dealing in illicit materials would be exposed.

The smuggling statutes and the National Stolen Property Act should be enough to shut down this market for illicit goods. If not, multilateral or regional agreements/statutes are yet another way to deal with the problem head-on. If museums want goods for display and education, the CPIA can provide for official diplomatic channels for long-term loans, currently a success under the Italy-US MOU. Let other legal instruments – the criminal ones – be those that deal with people and institutions trafficking in illicit materials, particularly people and institutions who do know better.

Bibliography:

Agurcia Fasquelle, R. 1998. “Copan Honduras: Looting in the Margarita Structure.” Mexicon 10(4): 68.

Arden, T. 2004. “Where are the Maya in Ancient Maya Archaeological Tourism? Advertising and the Appropriation of Culture.” in Yorke Rowan and Uzi Baram (eds.), Marketing Heritage: Archaeology and the Consumption of the Past. Altamira Press, New York.

Boone, E. H. (ed.) 1993. Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC.

Brodie, N. and C. Luke. 2006. “The Social and Cultural Contexts of Collecting.” in Neil Brodie, Morag Kersel, Christina Luke, Kathryn Walker Tubb (eds.), Archaeology, Cultural Heritage and the Antiquities Trade, pp.303-320. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, Florida.

Chinchilla, O. 1998. “Archaeology and nationalism in Guatemala at the time of independence.” Antiquity 72: 376-387.

Coggins, C. 1972. “Archaeology and the Art Market.” Science 175(4019): 263-66.

Edgers, G. and S. Pinto. 2006. “MFA agrees to return disputed art to Italy.” Boston Globe (31 July 2006).

Gerstenblith, P. 2001. “The Public Interest in the Restitution of Cultural Objects.” Connecticut Journal of International Law 16: 197-246.

Gilgan, E. 2001. “Looting and the Market for Maya Objects: a Belizean Perspective.” in Neil Brodie, Jenny Doole, and Colin Renfrew (eds.), Trade in illicit antiquities: the destruction of the world's archaeological heritage, pp.73-88. McDonald Institute Monographs for Archaeological Research, Cambridge.

Guenter, S. 2006. “Conversations: Site Q Discovered!” Archaeology 59(1).

2004. “The Never-Ending Story: More Looting at Dos Pilas.” Mesoweb News and Reports, available from: http://www.mesoweb.com/reports/ DPL/looting.html

Joyce, R. A. 2003. “Archaeology and Nation Building: A View from Central America.” in Susan Kane (ed.), The Politics of Archaeology and Identity in a Global Context, pp. 79-100. Archaeological Institute of America, Boston.

Kennedy, R. and H. Eakin. 2006. “For Met chief, no acquisitions regrets.” International Herald Tribune (1 Mar. 2006).

Luke, C. 2006. “Diplomats, Banana Cowboys, and Archaeologists in western Honduras: A History of the Trade in Pre-Columbian Materials.” International Journal of Cultural Property 13(1)25-57.

Luke, C. and J.S. Henderson, 2006. “The Plunder of the Ulúa Valley, Honduras and a Market Analysis for its Antiquities.” in Neil Brodie, Morag Kersel, Christina Luke, Kathryn Walker Tubb (eds.), Archaeology, Cultural Heritage and the Antiquities Trade, pp.147-172. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, Florida.

Luke, C. and M. Kersel. 2005. “The Antiquities Market": A retrospective and a look forward.” Journal of Field Archaeology 30(2): 191-200.

Mackenzie, S.M. 2005. Going, Going, Gone: Regulating the Market in Illicit Antiquities. Institute of Art and Law, Leicester.

Maudslay, A. P. 1889-1902. Biologia Centrali-Americana. 5 vols. London.

Matsuda, D. 1998. “The Ethics of Archaeology, Subsistence Digging, and Artifact Looting in Latin America: Point, Muted Counterpoint.” International Journal of Cultural Property 7(1): 87-97.

Mortensen, L. 2006. “Structural Complexity and Social Conflict in Managing the Past at Copán, Honduras.” in Neil Brodie, Morag Kersel, Christina Luke, Kathryn Walker Tubb (eds.), Archaeology, Cultural Heritage and the Antiquities Trade, pp.258-269. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, Florida.

Schuster, A. M.H. 1997. “The Search for Site Q.” Archaeology 50(5).

Stephens, J. L. and F. Catherwood. 1841. Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán. New York, Simon and Schuster.

Stuart, G. 1997. “The Royal Crypts of Copán.” National Geographic 192(6): 68-93.

US Customs and Border Protection. 2004. “What Every Member of the Trade Community Should Know About: Works of Art, Collector's Pieces, Antiques, and Other Cultural Property.” An informed compliance Publication.

Additional Photo Credit:

(fig.14): Cylinder Vase. Maya, Late Classic Period, AD 725-760. Place of Manufacture: El Petén, Ik’ polity, Guatemala, Motul de San José area. Earthenware: orange, red, dark pink, and black on cream slip paint. 23.5 x 12.4 cm (9 1/4 x 7/8 in.) MS1121; Kerr 1439. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Landon T. Clay. 1988.1177.

Author's Biographical Note: Christina Luke (PhD Cornell 2002) teaches at Boston University. In addition to researching legislation and the antiquities trade, she conducts archaeological fieldwork in Mesoamerica as well as western Turkey, supported by grants from the National Science Foundation. She recently co-edited Archaeology, Cultural Heritage and the Antiquities Trade (2006), and is co-editor of and contributor to the Antiquities Market column of the Journal of Field Archaeology.

This article appears on pages 46-54 of Vol.4 No.3 of Athena Review, and has been reformatted for internet publication.. The complete text and original format may be obtained in the printed version of the magazine.

Athena Review Image Archive™ | Archaeology in the News | Guide to Archaeology on the Internet | Free issue | Back issues

Main index of Athena

Review |

Subject Index

| Travel

Pages |

Galleries and

Museums |

Copyright © 1996-2008 Athena Publications, Inc. (All Rights Reserved).